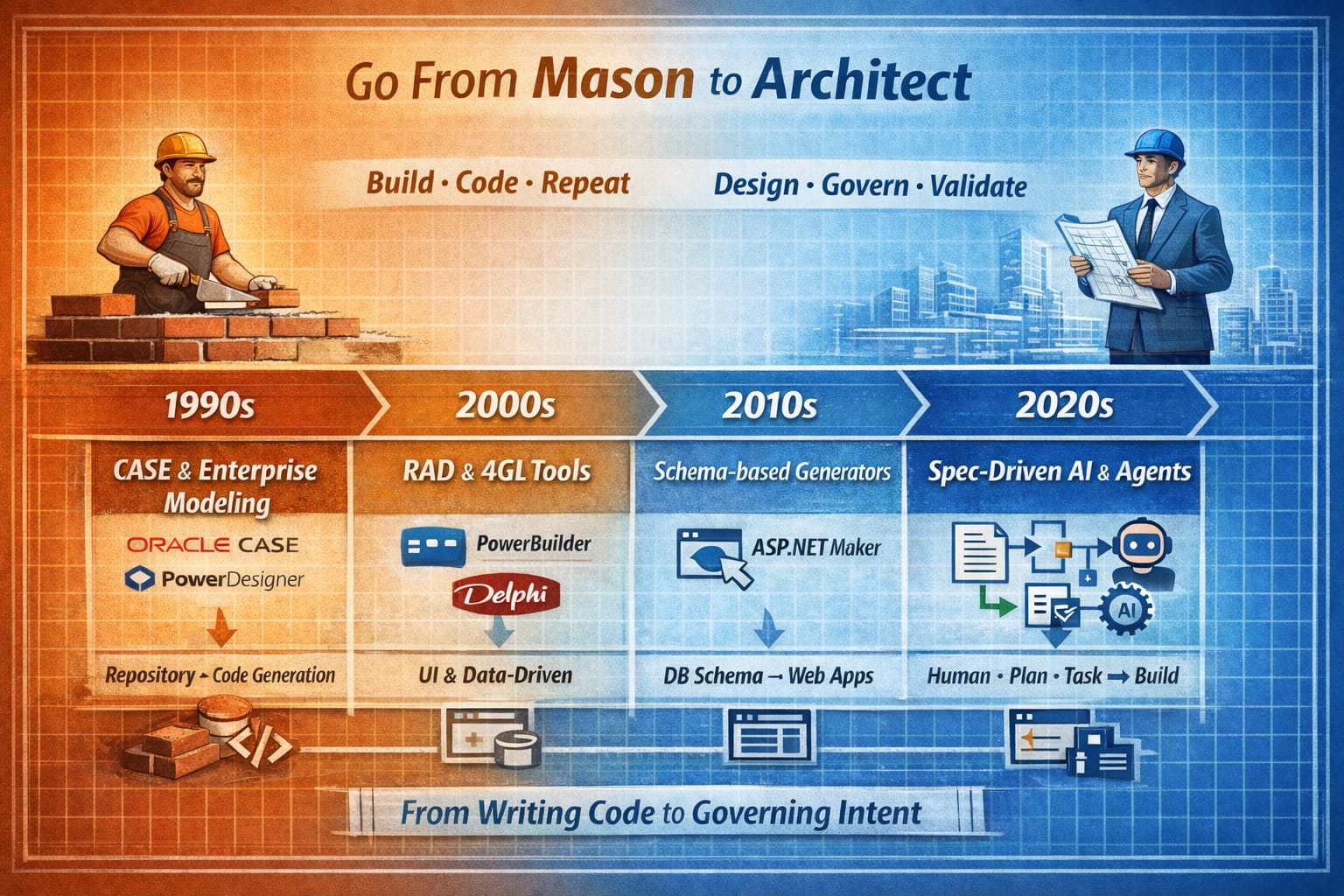

From Oracle CASE to Spec-Driven AI Development

From Oracle CASE repositories in the 90s to AI-powered Spec Kit today, this is a personal journey through four decades of model-driven development. Learn how the industry cycled from structure to speed and back to synthesis, and what Monday-morning practices you can adopt now.

Early in my career, I had the opportunity to work with tools that many engineers today have never experienced — environments where you didn't write code, you defined rules. Where a central repository governed truth. Where systems could be regenerated deterministically from a model. These were called CASE tools, and Oracle CASE was the one that changed how I thought about software forever.

At the time, they felt revolutionary. Looking back, I realize they were something even more important: they showed me what software engineering could look like when the model, not the code, was the center of gravity.

That lesson stayed with me for decades. And it explains why, when I encountered Spec Kit and modern AI-assisted development, my reaction wasn't excitement about something new. It was recognition. It felt like coming home.

The Early Foundation: When the Repository Was Truth

What made Oracle CASE powerful wasn't just that it generated forms or PL/SQL. It was the philosophy behind it. Quality didn't come from hand-crafting the code — it came from governing the model. The repository defined truth. Every screen, every table, every relationship flowed from that single source. As a developer, I was focused on intent and design, not on the repetitive mechanics of implementation.

Yes, these tools were often seen as clunky — heavy, proprietary, and rigid by modern standards. But the philosophy behind them was sound. That mental model changes how you see software forever. Once you've worked that way, it's very hard to go back to thinking of the source files as the thing that matters most.

S-Designer: Refinement and Regeneration as the Real Workflow

After Oracle CASE, I worked extensively with S-Designer — later known as PowerDesigner — and it expanded on everything I had learned, but it crystallized one idea I hadn't fully articulated before: the model is what matters, and regeneration after refinement is the secret sauce.

I wasn't maintaining code. I was maintaining a design. Every time requirements shifted, I went back to the model, refined it, and regenerated. The output was almost beside the point. What endured was the design artifact, not the implementation. That discipline — going back upstream instead of patching downstream — changed how I approached software development. It also made me deeply skeptical of any workflow that treated generated or scaffolded code as something you were supposed to edit by hand.

PowerBuilder: The Original Low-Code That Actually Worked

PowerBuilder approached the same idea from a more practical angle. Think of it as the original low-code platform before that term existed — declarative UI bound to database schemas, automatic SQL and CRUD behavior, rapid regeneration of working applications. It wasn't repository-heavy in the way CASE tools were, but it kept proving the same underlying point: high-level definitions can reliably produce working software.

It also reinforced something important about developer trust. When the generation was reliable and consistent, you stopped second-guessing the output and started investing more carefully in the inputs. That shift in attention — from reviewing what was generated to improving what drove the generation — is exactly the right place for a developer's energy to go.

ASP.NET Maker: Iterate on the Model, Not the Code

ASP.NET Maker brought these ideas forward into the web era, and it taught me something I still carry with me today. What it demonstrated wasn't just that you could generate a full CRUD web application from a database schema — it was that you should never edit the generated code. The moment you touched the output, you'd broken the contract. The right move was always to go back, refine the model or the configuration, and regenerate.

Iterate on the model, not the code. It sounds simple, but it cuts against a deeply ingrained instinct developers have to just fix the thing in front of them. ASP.NET Maker forced discipline because the alternative — a hand-edited generated file — was immediately fragile. That constraint was a feature.

The Middle Years: When Speed Meant Shedding the Model

Somewhere between the CASE era and today, the industry made a deliberate choice: shed the overhead, empower the individual developer, move fast. The heavy repositories and proprietary tooling of the 90s gave way to something fundamentally different — lightweight editors, command-line workflows, and developer productivity without a central model.

This wasn't loss. This was learning to move at a different speed.

VS Code became a text editor that could be anything you needed it to be, without forcing you into a specific methodology. It was the opposite of Oracle CASE. No repository. No regeneration. No enforced structure. Just you, the code, and whatever extensions you chose to install. The freedom was intoxicating after years of heavy tooling.

The command line came back into focus.

npm install

dotnet new

git commitDirect, immediate, unmediated. You weren't asking a CASE tool to interpret your intent and generate an artifact. You were issuing instructions and seeing results in seconds. The feedback loop collapsed from minutes to milliseconds.

DevExpress CodeRush taught me to navigate and refactor .NET code at the speed of thought, tightening that loop even further. IntelliSense wasn't just autocomplete — it was working at a higher level of abstraction, letting me think in concepts while the tool handled syntax. The .NET MVC scaffolding templates let me generate working application structures directly from a database schema — not as sophisticated as the CASE environments I'd come from, but fast, and just enough structure to get started.

What all of these tools had in common was that they optimized for individual developer productivity without the overhead of a shared repository or governance layer. You could clone a repo and be productive in minutes. No database to set up. No CASE workbench to install. No team repository to sync against. Just code.

The 90s solved the structure problem with centralized models and regeneration. The 2000s and 2010s solved the speed problem by giving that up and optimizing for individual velocity. Modern AI-driven development is the synthesis of both — the structure and governance of the old philosophy, married to the speed and lightweight tooling of the modern era.

Encountering Spec Kit: Recognition, Not Discovery

When I started working with Spec Kit, something clicked immediately — and now I understand why. Spec Kit restores the same foundational principles I'd been working with since the early CASE days. Human-readable specifications as the source of truth. Lifecycle governance around intent. Structured review before build. Deterministic implementation once clarity exists.

This wasn't a reinvention. It was the original promise of model-driven engineering, finally usable at organizational scale, without proprietary repositories or heavy tooling. The specifications are open. The governance is adaptive. The execution engine is AI. But the philosophy is the same one I recognized the first time I watched a CASE tool regenerate a consistent, correct system from a well-governed model.

But there's one critical difference that makes AI-driven development genuinely better than what came before.

The Critic: From Passive Walls to Active Partners

Here's the fundamental difference between the old CASE repositories and modern AI-driven development: the old tools were passive enforcement. They said no. The database schema didn't match the model? Error. Relationship violated referential integrity? Blocked. It was governance through constraint — a wall you couldn't cross.

AI governance is active engagement. It doesn't say no. It asks, are you sure?

One of my additions to Spec Kit — what I now call the critic prompt — stood out not just technically, but emotionally. It reminded me of the senior developers early in my career, the ones who always pushed back before you got too far down the wrong path.

Did you think this all the way through? What happens at scale? Is this solving the real problem, or just the visible one?

Great engineering cultures institutionalize that voice. But over the middle years, as teams grew and velocity became the primary metric, that voice got drowned out. The pressure to ship overrode the discipline to pause. Modern teams have lost it — not intentionally, but inevitably.

The critic prompt brings it back, not as a person, but as a repeatable governance mechanism. It asks the uncomfortable questions every time, without politics or fatigue. It's not a sycophant that always agrees with you. It's the senior architect who's seen this pattern fail before and wants you to consider the edge cases.

That's the evolution. The old tools were walls. The new tools are partners.

What the 40-Year Arc Actually Looks Like

Looking back at this journey — Oracle CASE in the nineties, S-Designer and PowerBuilder through the late nineties and into the two-thousands, ASP.NET Maker and the scaffolding era, CodeRush and IntelliSense as practical companions along the way, and now Spec Kit with AI execution — I can see the pattern clearly.

The 90s gave us structure. CASE tools proved that models could govern quality and that regeneration from a single source of truth was possible.

The 2000s and 2010s gave us speed. Modern IDEs, scaffolding, and iterative workflows made it possible to move at the pace of changing requirements.

Modern AI gives us synthesis. The structure and governance of the old CASE philosophy, married to the velocity and adaptability of modern development, with active rather than passive guidance.

The goal has always been the same: translate business intent into reliable software with minimal ambiguity and maximal consistency. What's changed is our ability to do it continuously, collaboratively, and at a scale that CASE environments could only approximate.

Where I Am Now — And What You Can Do Monday Morning

My rapid adoption of Spec Kit and subsequent Spec Kit Spark enhancements wasn't about chasing something new. It was about recognizing something old, reborn in a form that actually works for the way organizations build software today.

Oracle CASE taught me that models govern quality. The decades in between showed me what it costs when governance erodes — the architectural drift, the inconsistent patterns, the growing distance between business intent and what actually gets built. Spec Kit, and the AI-driven lifecycle it enables, showed me the path back.

I work differently now than I did in the nineties, but the instinct that drives how I work hasn't changed at all. Describe the intent carefully. Govern the model. Regenerate rather than patch. Let the implementation follow from clarity, not the other way around.

If this resonates with you, here's what I'd suggest:

- Treat your prompt library as the new repository. It's your source of truth. Version it. Govern it. Review changes to it the same way you'd review schema changes in the old CASE tools.

- Never edit the AI output manually. This is the same discipline ASP.NET Maker forced on me. The moment you touch the generated code, you've broken the contract. If the output isn't right, go back upstream. Refine the prompt. Refine the spec. Regenerate. Don't patch.

- Install a critic in your workflow. Whether it's a formal prompt like mine or just a checklist you run before committing, create a mechanism that asks the uncomfortable questions. Did you think this all the way through? What breaks at scale? What happens when this fails?

- Document the model, not just the code. Your future self — and your teammates — need to understand the why, not just the what. The specifications, the architectural decisions, the constraints that shaped the implementation: those are what endure.

That's what CASE taught me. That's what every tool since has reinforced in one way or another. And that's what I finally feel like I can do well — not just in pockets of a project, but across the whole lifecycle.